an op/ed piece by Jada Daniels, PhD candidate in Ecology at Louisiana State University & IOB co author of Introducing a Novel Course-Based Undergraduate Research Experience Using Duckweed as a Model System

I still vividly recall my undergrad days, and if there’s one thing I could change about them, it would be those endless hours in my Intro to Bio Lab. Sitting there, performing experiments straight out of a manual that seemed utterly disconnected from my lectures, let alone my overall perspective on science, was nothing short of a chore. Honestly? I loathed it. It felt like I was in a hamster wheel, picking up a skill one week and discarding it the next for a new one. I couldn’t see the point.

Fast forward to my graduate years, and my disdain for the traditional lab setup hadn’t waned. Being a teaching assistant only added to the monotony. It felt like I was now part of the very system I hated, perpetuating a cycle of pointless tasks and busywork without genuinely imparting any critical skills. That was until I was given the opportunity to teach a CURE class. CURE, for those not in the know, stands for Course-Based Undergraduate Research Experience. It’s not your typical follow-the-manual lab class. No, it’s something way more engaging and real. This program is a game-changer, integrating hands-on research projects right into the core of introductory biology lab courses. Having taught CURE for two years, the difference in students’ engagement and understanding is day and night.

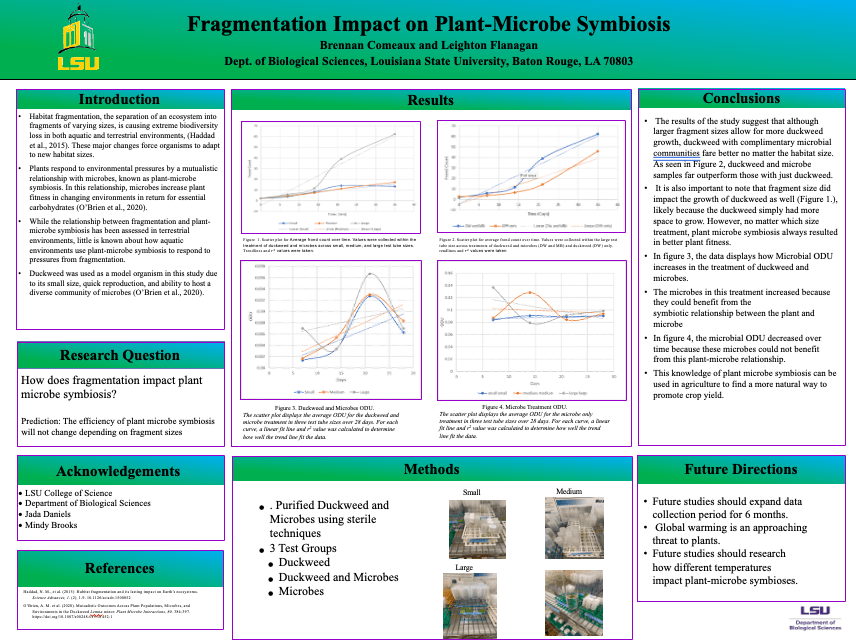

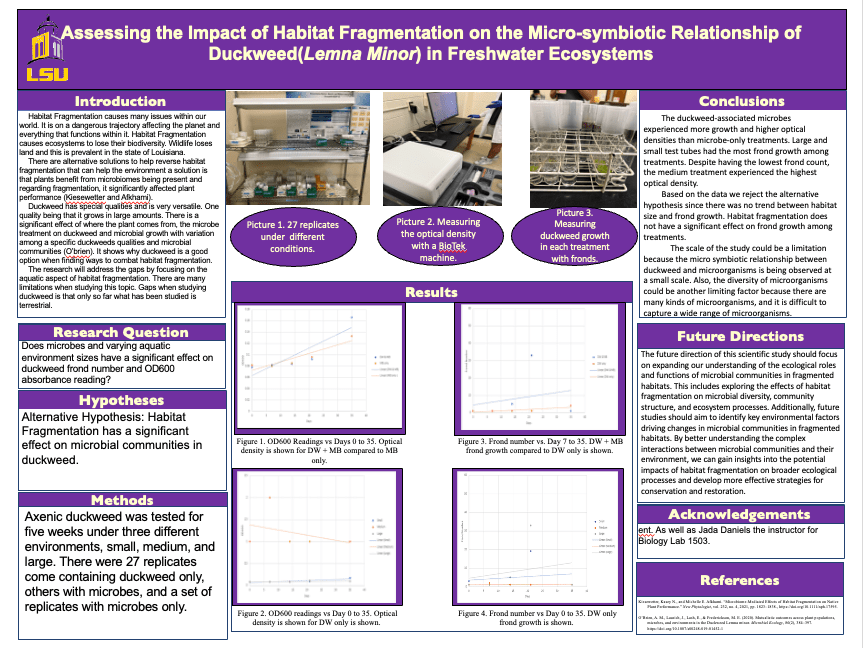

Take, for instance, a project I introduced based on duckweed. The objective? To understand how habitat size influenced microbial and duckweed growth. But instead of me handing out step-by-step instructions and giving out a DIY project kit, students were in the driver’s seat. Students began their hands-on experience by venturing outside to gather their own samples from ponds, collecting both water and duckweed. Using real-world samples, they returned to the lab, where a new set of challenges awaited them. Their first task was to produce axenic duckweed, a process that required precision and careful methodology. Following this, the students took the reins once more. It became their responsibility to plate and then streak bacteria colonies. Their ultimate goal was to create a polyculture, which would serve as the foundation for their individual experiments. Each step was crucial, demanding attention to detail and fostering a deeper understanding of the scientific process. They weren’t just following orders; they were pioneering their experiments.

I’ll never forget what one of my students, Andre Sfeir, said: “The idea that this project is mine is what makes me care.” That statement hit the nail on the head. By allowing students to craft and oversee their experiments, we’re nurturing a sense of ownership and responsibility that traditional labs just can’t offer. The old lab setup? It’s like they teach you to juggle, but as soon as you get the hang of it, they replace the balls with chainsaws. Skills are introduced and then swiftly thrown by the wayside. With CURE, though, students aren’t just passing through a class; they’re diving into projects with genuine interest. They care about their work because it’s theirs.

Incorporating the earlier sentiment, if we truly want to light a fire under the next generation of scientists, we must break away from the mold of those yawn-inducing biology labs. With programs like CURE, we’re not just going through the motions. We’re embracing genuine scientific exploration, and the results? Well, they speak for themselves. Students don’t just learn; they thrive.

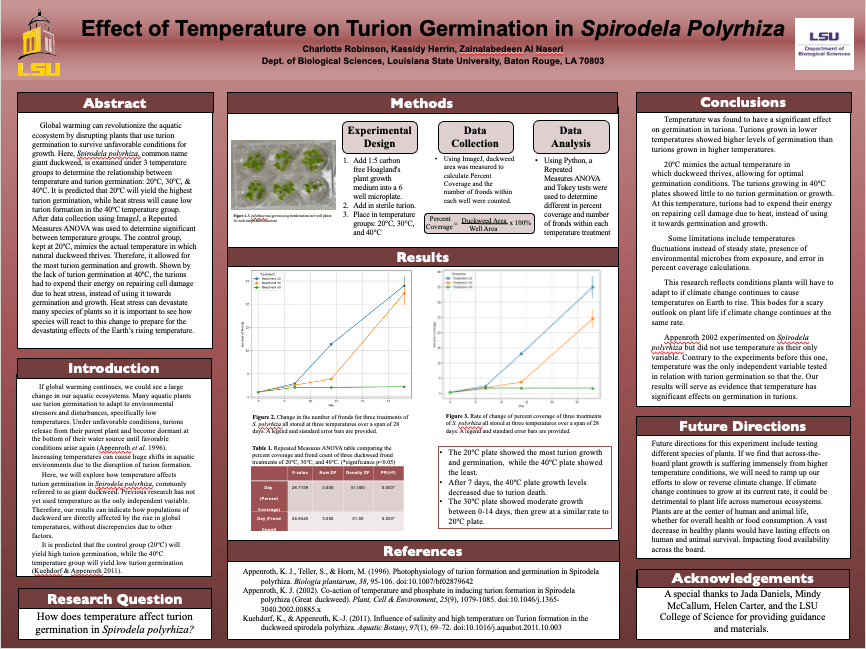

Their research led to some genuinely eye-opening results that felt like a step forward in our understanding. Here’s the gist: they took duckweed strains from three distinct habitats of varying sizes—small, medium, and large—and cultivated them in test tubes corresponding to those sizes. With both a microbial and non-microbial treatment, they let them grow for five weeks. The data revealed some very interesting patterns. Regardless of the microbial treatment or test tube size, it was consistently observed that microbial communities derived from the largest habitat exhibited the highest microbial density. Moreover, in the larger test tubes, duckweed consistently showed a notable rise in biomass, regardless of its source habitat or the given treatment. A clear trend was that duckweed’s growth rate was consistently higher when paired with microbial entities than when grown alone. Through the unique opportunities provided by CURE, we were able to achieve remarkable results not typically seen in traditional labs. Plus, the cherry on top? Students got to show off their work to the entire university at a poster session.

I know that changing the entire structure of lower-level class can seem time consuming, and maybe not even worth it for you. But try making small changes if you have the time. Change the way they perform experiments, or even just live outside of the lab manual for once. Trade out some busy work for a microscope lab. The options are endless, and your students will thank you for it.

Jada Daniels is a PhD candidate in Ecology at Louisiana State University, where she studies host-associated microbial communities using duckweed model systems. As a Graduate Teaching Assistant for BIOL 1209, she developed and implements a Course-Based Undergraduate Research Experience (CURE) that engages students in authentic investigations of plant-microbe interactions and environmental stress responses. Her work bridges ecological research and evidence-based pedagogy, with interests in democratizing science education and improving undergraduate research training in biology.

Connect with Jada:

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/jadadaniels/

Instagram: @jadatdaniels

BlueSky: @jadatdaniels