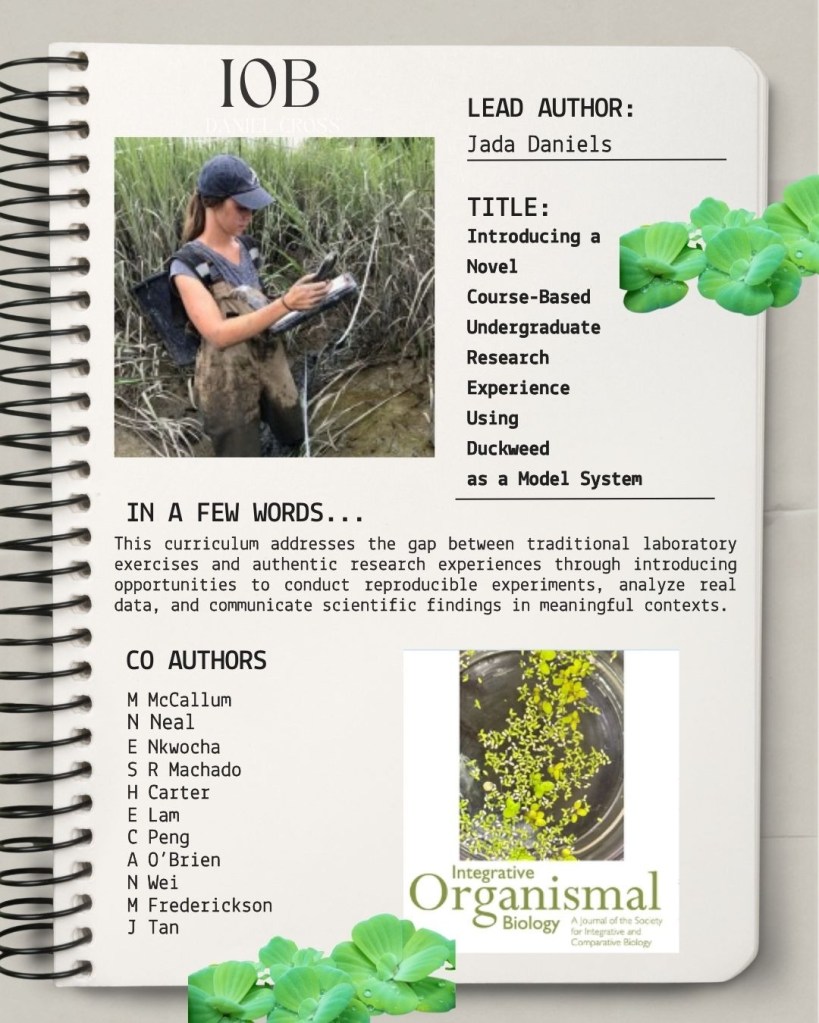

At IOB we like to spotlight not only the papers we publish but also the scientists behind those papers.

Below, lead co- author on ,

Jada Daniels answered several questions about her scientific journey.

Tell us a bit about your early interest in the sciences. Looking back, do you have a first experience or “aha” moment in school where you knew you wanted to pursue being a scientist?

During my undergraduate herpetology class, my professor Dr. Christian Cox completely transformed how I saw my future. I’d always been curious about the natural world. Growing up in a rural area, I was surrounded by ecosystems and organisms, but I didn’t see myself reflected in traditional science spaces. I originally started out on a pre-vet track just simply because I wasn’t aware of any other options. Dr. Cox helped me realize that research wasn’t some narrow, predetermined path reserved for a certain type of person. I could study almost anything that interested me. That realization was huge. It opened doors I hadn’t known existed and showed me that I belonged in science just as much as anyone else.

What do you feel were some of the surprising things you’ve learned along the way?

The most surprising thing has been discovering how many undergraduate students genuinely care about duckweed and microbes! As a grad student, you can get trapped in this mindset that you’re the only person in the world who finds your research interesting, that your work exists in this tiny niche. But semester after semester, I watch students get genuinely excited about plant-microbe interactions, duckweed, and environmental stress responses. They ask questions and find meaning in the same systems I study. It’s this powerful reminder that science isn’t as isolating as it sometimes feels. When you invite people in and show them why something matters, they care.

I’ve also been surprised by how much teaching has made me a better researcher. Designing the CURE forced me to think more clearly about experimental design, statistical approaches, and how to communicate complexity. The questions students ask, sometimes the naive ones, make me reconsider assumptions I’d stopped questioning. There’s this beautiful feedback loop between teaching and research that I never anticipated.

Were there any misconceptions you had about your field and or being a scientist?

I used to think that breakthroughs came from solitary geniuses working alone in labs, that real science was this isolated, individual pursuit. But that’s not how it works at all.

My best ideas have come from conversations with my advisors, with colleagues, with students who ask questions I hadn’t considered. Science is deeply collaborative and iterative, not a solo performance.

Jada Daniels

I also had this misconception that there was a “right” path into science: straight from undergrad to grad school, no detours. My path included working as a research technician with the USGS and Georgia DNA, teaching at a technical college, doing community outreach. These were experiences that felt off track or like detours at the time. But those experiences gave me perspectives and skills that make me a better ecologist and educator now. My rural background felt like a barrier initially, but I’ve learned that diverse perspectives don’t just belong in science. They’re essential for asking questions others might miss.

What are some of your goals (research and otherwise) for the future?

My primary research goal is to keep advocating for host-associated microbes and their importance in ecology. Microbiomes are so often left out of conversations about conservation and management, even though they’re fundamental to host health, ecosystem function, and resilience to environmental change. When we talk about protecting duckweed populations, or any host organism, we can’t ignore the microbial communities they depend on. I want to continue building evidence that microbial diversity isn’t just a side note; it’s a driver of ecological processes. My hope is that this research will influence how we think about conservation targets and management strategies.

Beyond research, I want to continue integrating authentic research into undergraduate education. The Duckweed CURE has shown me that students don’t just learn skills. They develop ownership over scientific questions and see themselves as contributors to knowledge. I want to help other institutions build similar programs, particularly those serving students who, like me, don’t see traditional pathways into science. If I can mentor students from underrepresented backgrounds and create spaces where diverse perspectives thrive, that’s as important as any paper I publish.

They say we learn best from our perceived failures. Can you detail for us a bit about a project or experiment that at the time you felt failed, yet when you think of it now, you learned from? (and what did you learn?)

One of my most frustrating patterns as a scientist has been having ideas that I don’t yet have the means to execute. Early in my PhD, I had this vision for a large-scale comparative project across different host systems, exactly the kind of work I’m doing now with public databases. But at the time, I didn’t have the computational skills, the statistical background, or the funding to make it happen. I felt stuck, like I could see where the science needed to go but couldn’t get there.

For a long time, that felt like failure. But what I’ve learned is that those premature ideas weren’t wasted. They were seeds. They forced me to build skills I didn’t have, to seek out collaborators who could fill gaps, and to be more strategic. That cross-system project I couldn’t do three years ago? I’m doing it now, because I spent those years learning coding languages, mastering analyses, and understanding how to wrangle messy datasets. The idea didn’t fail. I just wasn’t ready for it yet. Now I approach ambitious ideas differently. Instead of seeing them as immediate projects, I see them as roadmaps. What do I need to learn? Who do I need to talk to? What smaller steps build toward that bigger vision? It’s taught me patience, humility, and the value of incremental progress.

Who were some of your mentors over the years and what are some of the things they imparted to you?

Dr. Ray Chandler was my master’s thesis advisor at Georgia Southern University, and working with him was transformative. Ray was a pure naturalist, the kind of scientist who could walk into any ecosystem and just know what was happening. He had this encyclopedic understanding of natural history, but it wasn’t just memorized facts. It was this deep, intuitive sense of how organisms interact, how systems work, and how to observe patterns others might miss. What Ray taught me wasn’t just about ecology. It was about paying attention. He modeled this patient, careful observation where you don’t rush to conclusions but instead sit with the complexity of what you’re seeing. That ability to observe, to question, and to let the system teach you, that’s something I carry into my work with duckweed and microbes today.

Dr. John Carroll and Dr. Lance McBrayer, also at Georgia Southern, gave me something equally important: opportunities. They opened doors for me to do field work, to learn new systems, and to really get my hands dirty with research. They trusted me with helping on projects, and gave me the kind of hands-on training you can’t get from a textbook. They showed me that mentorship isn’t just about advising. It’s about creating space for people to grow.

I also have to mention my fellow graduate students during my master’s, Corina Newsome and Alex Troutman.

Newsome

Troutman

Watching them work was inspiring. They’re both so passionate about what they study and about including others in science. Being around people who genuinely cared about their research and about making space for others helped me beat imposter syndrome in those earlier stages. They showed me that you don’t have to choose between excellence and inclusivity. You can, and should, do both. That sense of community and mutual support has shaped how I approach my own mentoring now.

If you had to offer any advice to scientists starting out, what would it be?

Don’t wait until you feel ready. So many early-career scientists hold back because they think they need perfect skills or perfect credentials before they can contribute. But science is learned by doing. Take the opportunities that scare you a little. Say yes to the field work, the collaboration, the project that feels just beyond your current abilities. That’s where growth happens. Your non-traditional background is an asset. If you don’t see yourself reflected in traditional science spaces, that’s not a flaw. It’s a perspective others are missing. The questions you ask, the systems you notice, the barriers you identify, those come from lived experience. Science desperately needs diverse voices. Build your community early. Science can feel isolating, especially if you’re one of few people who look like you in your program. Find your people, whether that’s other grad students, mentors, or communities outside academia, who remind you why you started and support you when it’s hard. And finally, ideas come before tools. Don’t abandon a research question just because you don’t yet know how to answer it. Write it down. Hold onto it. Then build the skills, find the collaborators, and create the conditions to make it happen. Some of the best projects are the ones you weren’t ready for at that moment, but you will be.

Connect with Jada:

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/jadadaniels/

Instagram: @jadatdaniels

BlueSky: @jadatdaniels