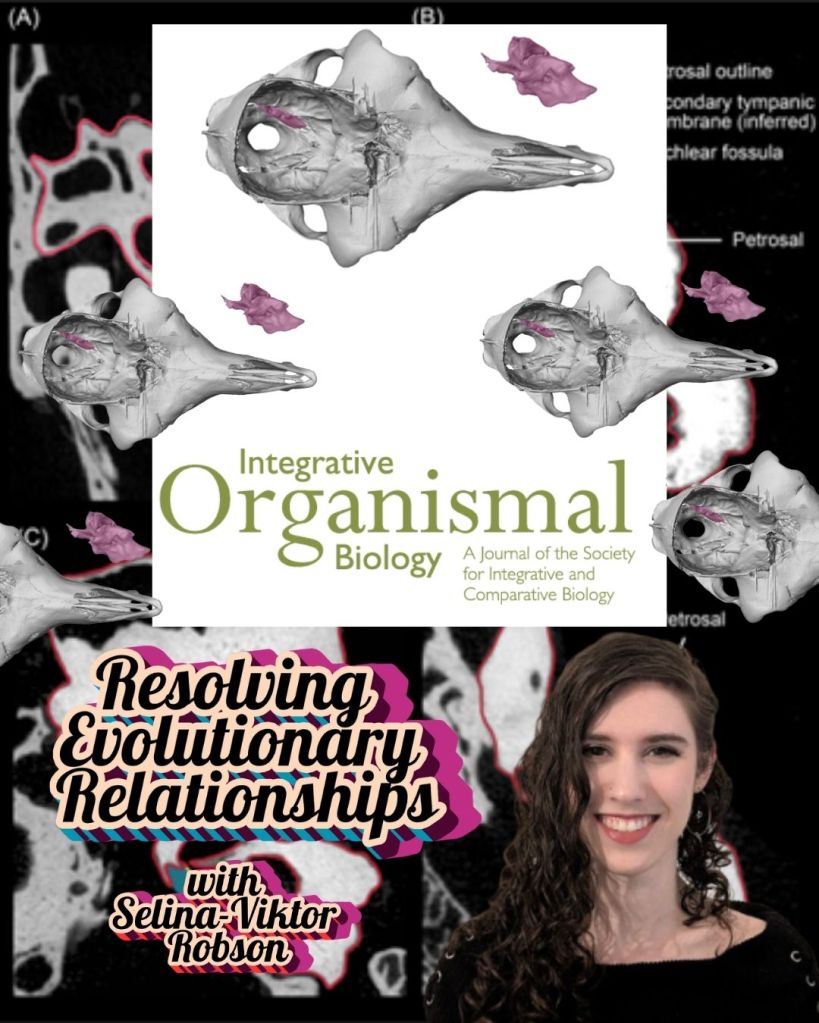

The Internal Otic Region of Oromerycids (Artiodactyla, Oromerycidae), Early Camelids (Artiodactyla, Camelidae), and the Vicuña (Artiodactyla, Camelidae), Including Notes on Intraspecific and Subadult Ontogenetic Variation

S V Robson , A Prokop , C N Baird , J A Ludtke , S T Tucker , J M Theodor

Integrative Organismal Biology, Volume 7, Issue 1, 2025, obaf043, https://doi.org/10.1093/iob/obaf043

Dr. Selina-Viktor Robson is a paleontologist who specializes in the evolution of even-toed hoofed mammals (i.e., artiodactyls) including well-known species such as llamas, cows, and pigs. Much of their work focuses on the internal ear region, a complex part of the skull that is useful for understanding sensory systems and evolutionary relationships. They are a guest researcher at the Leibniz Institute for the Analysis of Biodiversity Change in Hamburg, Germany where, along with continuing their research on artiodactyls, they are also working with Dr. Emanuel Tschopp to study the neck vertebrae of sauropod dinosaurs.

Selina-Viktor carved out some time to fill us in on some of the details surrounding this co-authored work:

1 Could you give a brief overview of what you feel the reader needs to know about this debate surrounding the taxonomic composition of the suborder Tylopoda to help them fully appreciate your work?

Over the centuries, Tylopoda has become a “waste-basket” into which many extinct families have been thrown, often without strong justification for doing so. The only living members of Tylopoda are camels, llamas, guanacos, alpacas, and vicuñas, all of which are part of the family Camelidae. Although the living species are native to Asia, Africa, and South America, the family actually originated in North America and spent the first ~40 million years of its evolution confined to the continent. Despite an exceptional fossil record, camelid origins are still shrouded in mystery because we don’t know which extinct groups are closely related to them. Without knowing this, we cannot determine which families are truly tylopods. Because these other groups are extinct, we can’t use molecular data to study them, so we must instead continue to search for anatomical clues. There have been decades of study on the teeth and bones of these purported tylopods with little resolution, and the internal ear region is one of the few promising avenues left—because it is inside the skull, it is not easy to access without CT scanning, making it a treasure-trove of previously unstudied data. We are hoping that the ear region can help us finally resolve which extinct families are really tylopods. It’s possible that Tylopoda is a massive suborder, but it is more likely that Tylopoda is tiny and contains only a few North American families, rendering many other families “orphaned” until further work is done.

2 What unforeseen dilemmas were there in accomplishing this work? And how did you resolve them or allow them to help you reform the work?

Much like Tylopoda itself, this started as a tiny project that grew to unwieldy proportions. Initially, we just wanted to study the internal ear region of oromerycids, an extinct North American family of small-bodied hoofed mammals thought to be closely related to camelids. We had already tested the other purported North American tylopods and our results had shown that their ear regions were distinct from that of camelids, so oromerycids were our last hope of finding ear region similarities. We started with an early oromerycid and quickly realized that it looked nothing like a camelid. However, we know that the internal ear region can change a lot within a family, so we decided to look at a later oromerycid as well, Eotylopus, and voila! It had an almost perfect mix of camelid and non-camelid features, exactly what one would expect from something closely related to a camelid. We were thrilled, but there was a problem…the specimen we were using was a juvenile. Juvenile specimens are fantastic for many reasons, but they may not look the same as an adult, so caution must be used when making evolutionary inferences. This was an issue, particularly given that this specimen was seemingly key in the ongoing tylopod debate. We decided to greatly expand our sample, both to check how the internal ear region changes during growth and to test whether the features in Eotylopus were consistently present in early camelids. In doing so, we ended up producing the most taxonomically expansive sampling of the camelid ear region to-date, conducting a study of camelid ear region ontogeny, discovering potential genus-level differences in the ear region of early camelids, and uncovering a surprising amount of variation within species and genera. Also, this appears to be the first published study extensively detailing the inner ear region of a living South American camelid (the vicuña), at least when it comes to the petrosal bone and the bony labyrinth. All-in-all, what started as a straight-forward comparison grew into a monster of a project, but we believe that our paper is much stronger as a result. It feels as if the data wanted to tell a story and we were just along for the ride.

3 What implications do you feel your work will have for future morphologists?

Our work strongly demonstrates the importance of sampling multiple individuals when studying the internal ear region. This is because we detected much more variation in the region than has been previously reported. In some ways, this is rather inconvenient because CT scanning can be expensive and when working with fossils, sometimes only one individual is available, but it is an important result nonetheless. By documenting such variation, we can help morphologists who only have access to one specimen ground their inferences by determining which features are more likely to be variable within species and genera. This makes all of our research stronger because it is allowing us to sift through the morphological “noise” and identify what is meaningful to the questions we are asking.

On perhaps a less onerous note, it also appears that older juveniles can reliably be used in studies of the internal ear region, at least for even-toed hoofed mammals up to the size of a vicuña. Before this, it was known that juveniles of very small hoofed-mammal species (e.g., mouse deer and musk deer) could be used, but there were concerns that animals with a larger body size might show more changes in their bony ear region because of bone accretion during growth. It is still possible that such changes occur for large-bodied species such as camels and cows, but our results demonstrate that it is unlikely to be a problem for medium-bodied species. This is reassuring and should make it easier for future morphologists to include juveniles in such studies.

4 In what ways has new technology allowed more work like this to be done? And what is on the horizon with tech that could assist even more so?

With CT scanning, we can non-destructively image a specimen and create 3D digital models of structures, even those not visible on the surface. Because the internal ear region is inside the skull, it used to be that you would either have to hope to find an isolated petrosal bone (a major bone of the ear region), a skull that was broken in just the right way, or destructively sample a specimen through physical dissection. None of these options are ideal. Now, CT scanning allows us to study the structures without damaging the specimen, and it makes the reconstruction of tiny empty spaces such as the bony labyrinth (a hollow cavity in the petrosal bone that contains the inner ear in life) much easier and more accurate. New methods are constantly being developed that make the segmentation of the CT data faster, allowing for more throughput and less time spent on processing individual scans. The speed at which even poor-quality scans can be processed will likely greatly increase in the next few years. Technological advancements are also constantly making CT scanning cheaper and faster with higher resolution and better contrast, improving the quality of data while decreasing the time and monetary cost. For research such as ours, we typically use relatively small CT scanners, but linear accelerators and industrial CT scanners are also becoming more prevalent for imaging massive specimens, which is very exciting to see.

5 In your work you noted : “The results of this study have both positive and negative implications for the use of otic region data for phylogenetic inference.”

Do you feel overall, the results leaned one way or the other? More positive or negative and why?

Arguably, the results lean more negative than positive, but I think this is a short-term problem. As I mentioned before, we have found that the internal ear region has a lot more variability than previously thought, meaning that one individual is unlikely to capture the full range of variation within a species or genus. This can be a problem when doing a phylogenetic analysis because including such variation is important, but you can’t easily do that if you only have one example. However, there are ways to mitigate this. We would naturally recommend using multiple individuals whenever possible, but we recognize that it is not always so simple, particularly when working with rare fossils. Even in this study, we had several taxa represented by single individuals because they were the only known specimens with an intact ear region. In these cases, it is up to us researchers to determine how we want to handle our analyses, which in turn is dependent on what we want to test. Knowing that there is likely a lot of undocumented variation allows us to approach this problem better informed and, as our understanding of ear region variation and the development of new phylogenetic methods continues, it is likely that we will find new ways to handle such unknowns. So, while this ear region variation might have negative implications at the moment, in the long-run, this will hopefully serve to make our phylogenetic inferences more accurate and help to drive new research.

Connect with Selina -Viktor on LinkedIn