IOB co-author Paul J. Byrne aims to illuminate the processes that underlie the phenotypic and developmental changes within vertebrates and their resulting influence on physiology with his research. His dissertation was focused on the origin and evolution of the cardiopulmonary system of archosaurs. His postdoc is focused on the cytoarchitectural and neuroanatomical differences between two different chicken breeds to better understand the evolution of avian and nonavian dinosaur brain/skull integration. Below, he gives us some insights into his recent IOB work:

Evidence for the loss of pneumatization and pneumosteal tissues in secondarily aquatic archosaurs

P J Byrne , N D Smith , E R Schachner , D J Bottjer , A K Huttenlocker

How do you feel this current IOB work illuminates the processes that underlie the phenotypic and developmental changes within vertebrates?

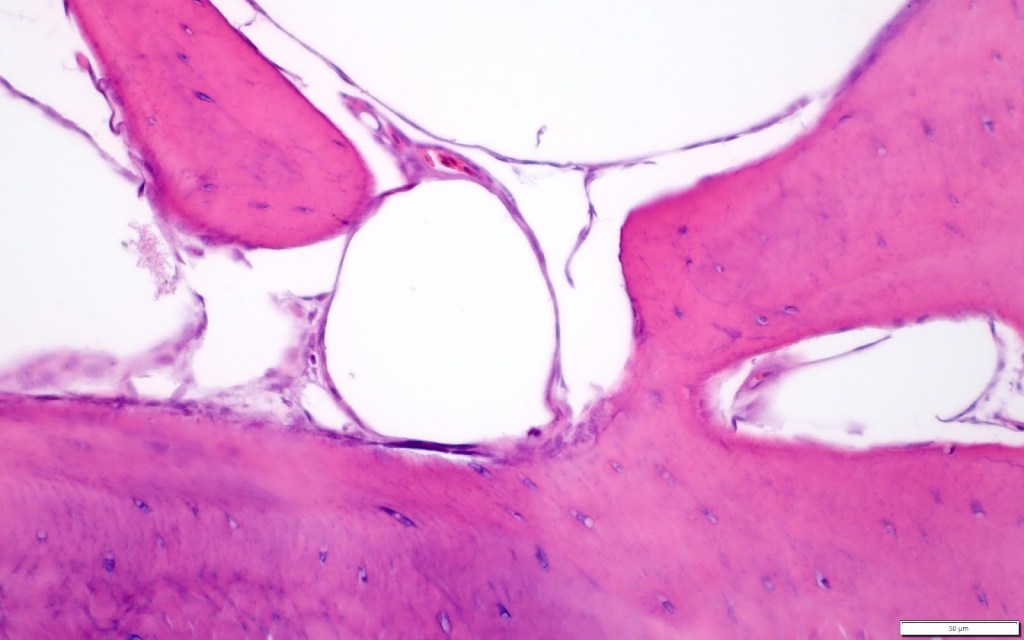

My co-authors and I are particularly excited to present our new study describing the presence and absence of pneumosteal tissue in extant archosaurs. Pneumosteum represents fine-anchoring fibers that indicate a direct interaction between pneumatic diverticula (tissue extensions that branch from the air sacs and lungs of birds) and the secondary endosteal and trabecular surfaces of bone. This is really exciting because knowing where this tissue is present, and how its morphology varies, allows us to bridge an important gap between how complex, soft tissue structures associate with externally visible morphological features in bone. This is important contextual data that can be used in future studies to better understand the evolution of the avian respiratory system in extinct non-avian dinosaurs.

What theories do you have about why ventilatory air sacs and associated diverticula are lost when transitioning to an aquatic lifestyle or in small-bodied birds?

That’s a great question! When bone is pneumatized in extant birds, space once filled with dense trabecular bone and marrow is instead filled with lightweight, air-filled diverticula. Creating ‘hollowed out’ bone is particularly useful for volant birds because it helps allow for flight. Not all birds are pneumatized equally, however! The degree of pneumaticity, or ‘hollow-ness’, can vary based on the ecology and lifestyle of a bird. For example, when transitioning to an aquatic lifestyle, vertebrates undergo a suite of microstructural changes within bone (i.e., vascular organization and density) to offset the effects of buoyancy. Some species of penguin, such as the Emperor Penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri), can dive to depths of up to 600 meters for periods of 10 to 12 minutes (Kooyman and Ponganis, 1997). Having air-filled bones would restrict a penguin’s ability to perform these deep dives. In small-bodied birds, explaining the loss of pneumosteal tissue becomes a bit more complicated. Honestly, we are still unsure why small birds lack pneumosteum. However, because the lungs in birds are completely rigid and fixed, but the air sacs are highly compliant, we hypothesize that scaling relationships between body size and the respiratory system are likely part of the answer. However, this has yet to be tested. This represents an exciting avenue for future work. Better understanding how patterns of soft tissue pneumatization are represented in extant birds may illuminate how hard and soft tissue systems interact and adapt to different ecologies, including across land-to-sea transitions.

What inadequacies (or fallacies) have there been, in your opinion, in the past when scientists have set out to reconstruct the pulmonary anatomy of extinct birds and non-avian dinosaurs?

This one comes up a lot among colleagues and at conferences. It is falsely assumed that every non-avian dinosaur that has large fossae within the vertebrae exhibits bird-like air sacs and that every non-avian dinosaur without pneumatic osteological features does not have air sacs. The fact is, we simply don’t know! While pneumatic foramina are unambiguously associated with pneumatic diverticula, large lateral fossae can be reservoirs of fat in non-pneumatic archosaurs, like crocodylians. Meanwhile, apneumatic birds like penguins have a fully functioning system of air sacs that do not pneumatize the skeleton. In addition to this, birds have varying patterns of pneumatization, meaning that different diverticula bodies can pneumatize, or not pneumatize, specific skeletal elements.

For instance, let’s say you find an ostrich that has vertebrae pneumatized by only the lungs, but none of the air sac diverticula. If you were just examining the bones of this ostrich, you may incorrectly assume that it was pneumatized by air sac diverticula. That has become the case with fossils — it is too easily assumed that postcranial skeletal pneumaticity equates to a fully-fledged avian air sac pulmonary system. However, we don’t know whether or not non-avian dinosaurs had a different number of air sacs or if these air sacs pneumatized the skeleton at all. What we can tell, however, is that unambiguous osteological correlates for the pulmonary system (e.g., pneumatic foramina) let us know that pulmonary diverticula is associated with the skeleton, regardless of which part of the pulmonary system it originated from.

When did you first become aware there was a need for new evidence to help reconstruction be more accurate?

At the beginning of my Ph.D., I was fascinated with the evolution of the respiratory system in non-avian dinosaurs. I look up to many of the wonderful researchers who built a solid foundation of this work (e.g., Drs. Patrick O’Connor, Emma Schachner, Drew Moore, Nathan Smith, Matt Wedel…), and after conversations with them, realized that much more work was needed to be done in extant birds so that we can more confidently reconstruct the soft tissue of the respiratory system in extinct non-avian dinosaurs. After much discussion with my advisors, we decided that better resolving the microstructure of the attachment sites between diverticula and bone would be a fantastic way to contribute to the growing collection of work describing how soft tissue interacts with bone.

What implications for further research did this work lead to and will this be your next focus? If so, how will you go about beginning it?

This work has led to a suite of wonderful ideas that can help my collaborators and me better understand the evolution of soft tissue systems in birds. Right now, I am doing a postdoc focusing on learning techniques in evo-devo, with a continued focus on the evolution of soft/hard tissue interactions in birds. My next steps include submitting an NSF Directorate for Biological Sciences (BIO) proposal to apply for funds to use these embryological techniques to investigate more topics related to this. This really excites me, and I hope to do more work related to this in the near future. Furthermore, I am also grateful to my collaborators at the Department of Disease Investigations at the San Diego Zoo, who helped greatly with this work and hosted me in their lab. I have a newfound appreciation and insight as to how investigating large-scale macro-evolutionary questions related to anatomy can have a trickle-down effects that benefit the fields of conservation biology and pathology. I hope I can continue discovering how my work in evolutionary biology can help reveal the beauty of the natural world around us, and at the same time, preserve its diversity for generations to come.

Get to know more about Paul & The Burk Museum write up