by Caleb Gordon, MPhil, B.A.

Some species are easy to tell apart. Take chimpanzees and humans, for example. We are each other’s closest living relatives, we share the vast majority of our DNA, and we can still easily tell chimps apart from humans.

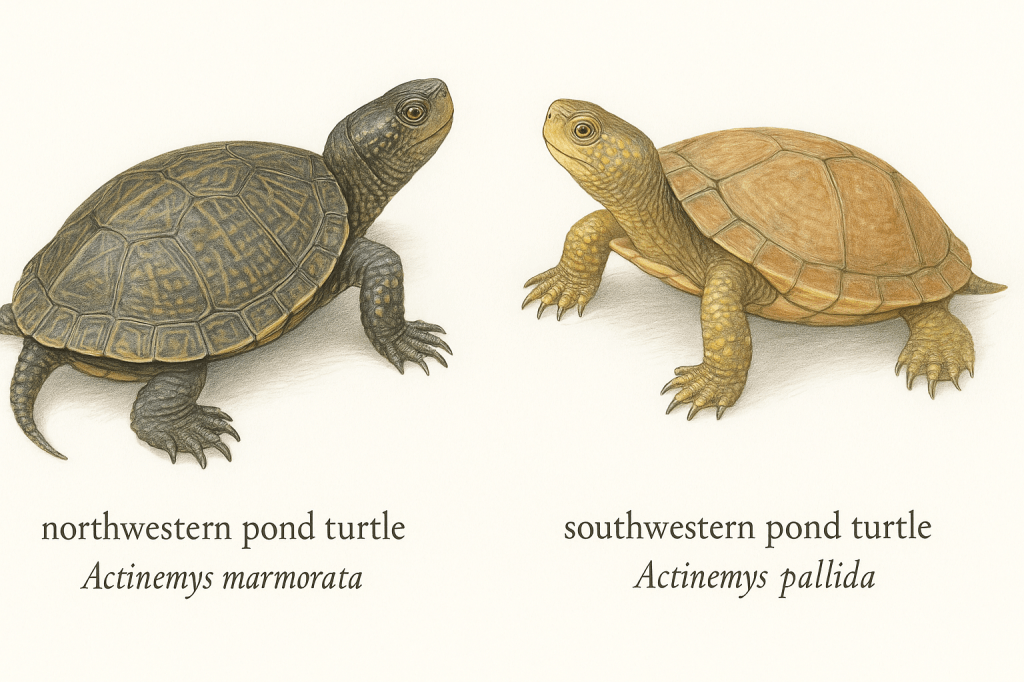

But for some species, the task isn’t so easy. Take the two turtle species below, for example. How would you tell them apart?

If you’re not sure, you’re in good company, because most scientists aren’t sure either. We call species like this “cryptic”, because no obvious external features help us distinguish them.

Sure, we can sequence their DNA and use that info to tell them apart, but this line of evidence isn’t always conclusive, and it’s often unavailable to scientists in the field. Sometimes scientists need to identify species by just looking at them. This is particularly important for conservation. Cryptic species often have slightly different geographic ranges and different conservation priorities, which inform how we protect them.

In order to conserve these cryptic species effectively, we need to be able to tell them apart, sometimes just by sight. And to do that, we need to know what visual differences we’re actually looking for. Unfortunately, for cryptic species like the two western pond turtles above, we don’t know what differences to focus on.

Computers to the rescue?

We humans often rely on computers to see differences that we ourselves can’t. I can’t tell apart the two barcodes for green grapes and purple grapes when I’m buying groceries, but the self-checkout machine can! So maybe our pond turtles are like bar codes… Even if we can’t tell cryptic species apart by ourselves, maybe a computer can tell them apart for us!

Since the 1950s, computer scientists have used supervised “machine learning”1 algorithms to make predictions. A supervised machine-learning algorithm is just any technique that uses observations about known things to make predictions about unknown things. And we can have computers do these for us over and over again until they make great predictions.

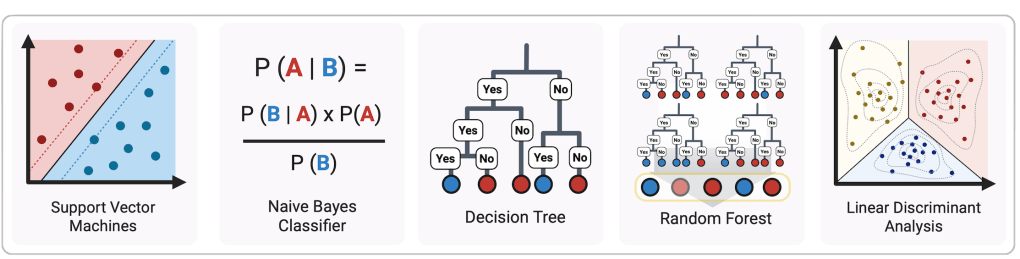

There are many ways for the computer to do this—many different sorts of supervised machine-learning algorithms.

These machine-learning methods (MLMs) all work differently, and have different strengths and weaknesses that we don’t need to go into. All we need to know is that they’re different techniques for classifying un-classified (or “unknown”) things based on already-classified (or “known”) things.

All five of these techniques have been used for decades to make helpful predictions in a variety of contexts. So, what if we can use them to tell apart those two cryptic turtle species, and other cryptic species like them?

In a recent study, published last year in Integrative Organismal Biology, Drs. Robert Burroughs, Kenneth Angielczyk, and their colleagues asked this very question.2

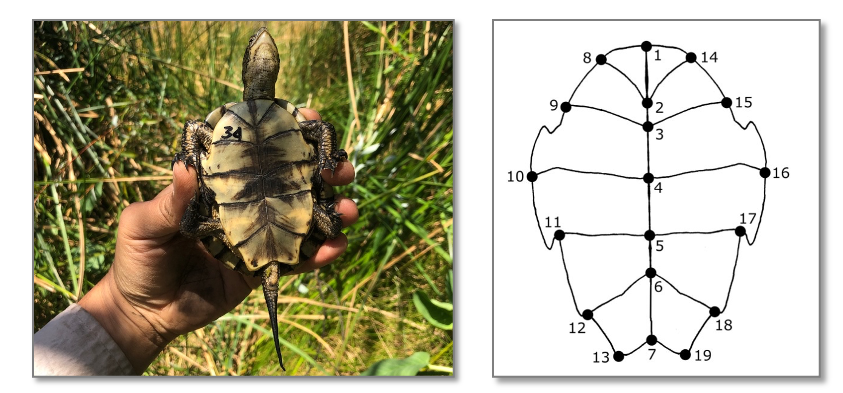

These researchers quantified the shape of each turtle’s under-shell (its “plastron”), for hundreds of these turtles. They then sorted their samples into different species clusters based on competing evidence from DNA data and morphology. And they used machine learning to assess whether under-shell shape accurately predicted any of these classifications.

In particular, they tested the ability of each of the five supervised machine-learning methods (MLMs) pictured above to predict each of the different classification schemes proposed by previous researchers.

To make sure these MLMs were generally good at distinguishing different species, they also tested their ability to predict the known classifications of other closely related (but non-cryptic) turtle species in the same family as our two cryptic pond turtle species.

Could MLMs tell the cryptic species apart?

In theory, yes! In practice, while MLMs could tell them apart better than you or I could, they still couldn’t tell them apart as well as we’d like.

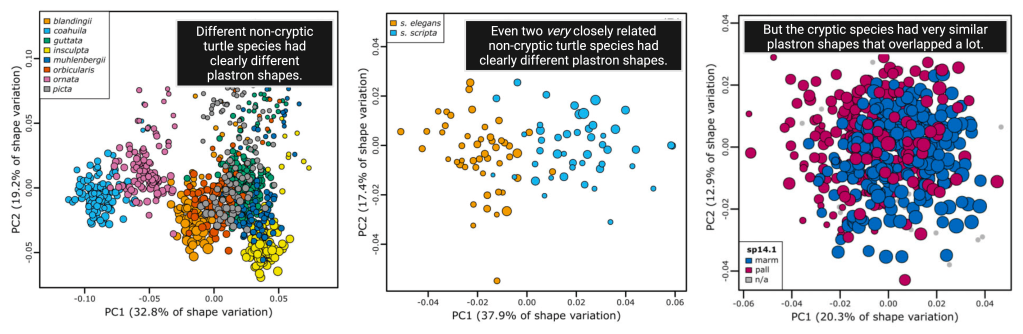

When Dr. Burroughs and colleagues plotted all the turtle shells from cryptic and non-cryptic species in shape space, one thing was clear: Non-cryptic species had very different shell shapes, but the two cryptic species (the southwestern and northwestern pond turtles) had hopelessly similar shell shapes.

This means that if you or I tried to tell the cryptic species apart by under-shell shape, we’d probably fail or die trying. Frankly, if we guessed which species was which five different times, our guesses would be right on average about 50% of the time. So how did our five MLM helpers do?

Well, consistently better than you or I would have! Burroughs, Angielczyk, and colleagues found that the five MLMs produced pretty consistent results, indicating that for this kind of species-classification problem, all of them work similarly well.

All MLMs were very good at distinguishing non-cryptic species (with average predictive accuracies of about 94% and 90% for emydine turtles and closely related Trachemys species, respectively.

And the MLMs were also pretty good at distinguishing the cryptic species. Previous studies have split the cryptic species up in different ways based on genetic data, and for one of these previous classifications (the “SP14.1” scheme in the paper), MLMs could predict cryptic species with an average predictive accuracy of about 81%!

That might not sound like a lot to a data scientist. We tend to be tough on machine-learning algorithms, and expect high predictive accuracies from them. But given that you or I would have correctly guessed the species of maybe 50% of those turtles, the MLMs’ 81% good guess rate strikes me as a big win.

Why do we care?

Why do we care about whether MLMs can tell cryptic pond turtle species apart? Well, this is good news for conservation. And conservation could use some good news.

Right now, human activity is causing a slew of global environmental problems (pollution, habitat destruction, overharvesting, and climate change) that have precipitated a major mass extinction.1 Many species are endangered by this extinction—including more than half of all known turtles2,3—and conservationists are trying to stop them from dying out.

Now, to protect an endangered species, a conservationist needs to know that it exists. They need to be able to recognize it, and tell it apart from any similar, closely related species. Unfortunately for conservationists, many cryptic species are almost impossible to recognize.

In the (ever nearer) future, hopefully MLMs can help these conservationists out. By testing the utility of these MLMs to detect cryptic species, Dr. Burroughs, Dr. Angielczyk, and their colleagues have brought us one step closer to using MLMs in conservation. With any luck, cryptic species will be easier to spot and thus easier to save.

References Cited

- Samuel, A. L. Some Studies in Machine Learning Using the Game of Checkers. (1959).

- Burroughs, R. W., Parham, J. F., Stuart, B. L., Smits, P. D. & Angielczyk, K. D. Morphological Species Delimitation in The Western Pond Turtle ( Actinemys ): Can Machine Learning Methods Aid in Cryptic Species Identification? Integrative Organismal Biology 6, obae010 (2024).

- Ceballos, G. & Ehrlich, P. R. The misunderstood sixth mass extinction. Science 360, 1080–1081 (2018).Rhodin, A. G. J. et al. Global Conservation Status of Turtles and Tortoises (Order Testudines). Chelonian Conservation and Biology 17, 135 (2018).

- Stanford, C. B. et al. Turtles and Tortoises Are in Trouble. Current Biology 30, R721–R735 (2020).

Caleb Gordon is a paleobiologist at Yale University who studies reptile evolution. He recently defended his PhD and will graduate in just a few weeks. For more info, feel free to check out his website!