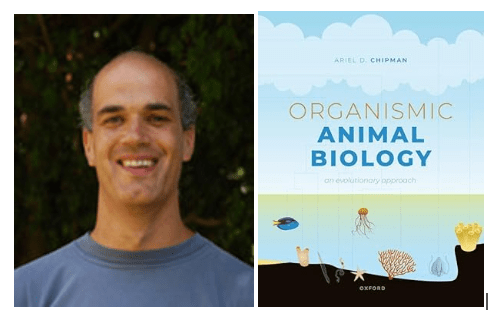

At IOB, we endeavor to highlight all the work our authors are involved in. Co author Ariel D. Chipman of

Serial Homology and Segment Identity in the Arthropod Head

Oren Lev, Gregory D Edgecombe, Ariel D Chipman

has a recent book Organismic Animal Biology (published by OUP) and he took time out to tell us a bit about it below.

Why do you feel modern biology teaching has tended to focus on the cellular and molecular level, majorly neglecting the organism?

If you look at the history of biology, there tends to be a pendulum motion swinging back and forth between a more mechanistic/molecular focus and a more holistic/organismal focus. The recent excitement over genome biology and computational and big data projects has led to a neglect of the more holistic approach. Some of the more computational biologists have even gone so far as to claim that we don’t need to do any more experiments, since all of the answers can be found in big data sets.

In parallel with this approach, I feel there has also been a renaissance of organism-focused biology. This can be seen in the appearance of new journals (like IOB) and new societies (like the International Society of Invertebrate Biology), and in the increasing use of modern genomic and computational approaches for answering century-old questions in organismic evolution. Organism-focused biology is still far from being mainstream, but it is by no means dead.

Undergraduate teaching will always tend to focus on what universities perceive as the most mainstream aspects of biology. It is important for teachers to realize both that organism-level biology is crucial to understanding all of biology, and that as a discipline it is still active and new discoveries are being made all of the time.

How did you set out to procure the handpicked examples to provide an overview of the diversity of animal life for this book?

There wasn’t a conscious process of picking examples. The book is largely based on a course that I have been teaching for over 15 years. Courses evolve over time with new ideas and examples replacing older ones that don’t fit the course narrative as well. I am not sure I can point a finger to the exact point over the years that a specific example entered the course (and ultimately the textbook). In some cases it was a talk I heard at a conference that seemed like a cool example worth incorporating. Some of the other examples in the book are classical examples that have been used in textbooks for years, although I mostly adapted the details to fit the focus of the book. Some ideas came from TAs, who were also graduate students working on specific organisms, and their research made it into the course. Some cases were purely practical – we were able to procure some organism for demonstration in the lab module accompanying the course, and that organism became part of the curriculum.

Were there species in particular that you felt lent themselves well to showcasing your ideas?

Not really. The beauty of organismic biology is that one can use almost any organism to demonstrate biological principles, since every organism needs to be adapted to and function within the same set of biological rules.

Although I initially trained as a vertebrate biologist, I have been working on arthropods for most of my career – since my post-doc – so I am naturally biased towards them. Because of their diversity and modularity, arthropods can provide numerous examples for almost any biological principle. Nonetheless, I tried to keep the book more general and not too arthropod-focused. Since the book follows a dual track; organism diversity on the one hand and biological principles and systems on the other, I tried to always give examples from taxa that had already been covered.

For anyone thinking of authoring a textbook, what would you say are some of the pitfalls they might encounter and how do you recommend tackling those?

Obviously, like any major endeavor, writing a textbook is a much greater commitment in time and focus than one tends to think initially. It really has to be the main thing you are doing, and if it is not the main thing, you have to consciously allocate time where that is the only thing you do. In my case, the book was mostly written in a series of self-imposed writing retreats, mostly during the holidays and the summer break. I went off by myself to somewhere far away where I sat undisturbed and wrote. I often combined these trips with conferences or academic visits, but even then, I always made sure there was a block of several days where I had no other commitments.

The second challenge, which is ongoing, is the need to market your book. If you’ve written a textbook and nobody uses it, you have just wasted several years of your life. Unfortunately, most publishers shift much of the onus of promoting the book to the authors. Getting a textbook into circulation is a process that takes several years and requires a lot of active pushing of the book, something most full-time academics don’t have the time or the skills to do properly. Whenever I go to a conference, I walk around with a copy of the book in my backpack and show it to everyone I meet. Hopefully, through these activities, the textbook will eventually catch on and be used by more and more undergraduate biology programs.

Purchase Ariel’s book via