By Tucker Heptinstall

Iobopen.com is hosting a series of blogs based on an article from Outside about “Awe” being good for the brain. We asked IOB authors to share their moments of “Awe” in the field. Read our second installation below by IOB coauthor Tucker Heptinstall.

It was a warm summer morning on Florida’s Little St. George Island off the coast of Apalachicola. I was working as an intern with the Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve (ANERR). Typically, I would be spending my morning conducting surveys on the beach for sea turtle nests; however, today was no typical morning. While sea turtle surveys were exhilarating, my heart had long belonged to snakes. ANERR was hosting a team of herpetologists looking to study the venom composition of the island’s pitvipers, with a particular emphasis on the largest rattlesnake in the world— the Eastern diamondback rattlesnake, Crotalus adamanteus. This was a species I had spent countless hours searching for, so when the opportunity to guide the biologists for the day arose, I eagerly seized it.

Little St. George Island is only accessible by boat, and my excitement about finding Eastern diamondbacks rose as the sun began to peak over the horizon and we motored our way across Apalachicola Bay. Upon our landing, we quickly sorted a mountain of field gear consisting of snake hooks, bags, tubes, buckets, and venom cups. Just as the sun began to light up the island, we set out in search of our target snakes.

We looked hard that morning. We hiked for miles through the sharp vegetation and sandy terrain of Little St. George, but the island was not willing to give up its secretive serpents. It was already mid-day, and we were hot, tired, hungry, and empty handed. The excitement we felt during the cooler morning air had begun to fade. Unwilling to give in, we took a lunch break and moved to a different area of the island.

Our post-lunch hikes were even harder. Temperatures were hovering around 95°F (35°C), and we were beaten by the Florida sun. It was late afternoon, and we had hiked a total of sixteen miles (25.75 km) across the island. Despite our efforts, all Little St. George was willing to give us in return were a couple of garter snakes (Thamophis sirtalis) and coachwhips (Masticophis flagellum). Not our target species. Our time on the island was running out, and my hope of catching a glimpse of C. adamateus, let alone catching one to extract venom,had waned.

Our group reluctantly made our way back towards the boat dock having resigned to the fact Little St. George was unwilling to share its venomous snakes with us today. However, it was at that moment our luck began to change, as a large cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus) crossed our path. It wasn’t our primary target, but its venom represented valuable data that we eagerly collected to ensure we didn’t return to the mainland empty handed. Little did we know, Little St. George was about to present us with a parting gift.

Walking down the bayside shoreline towards the boat, our group was stopped in our tracks and invigorated by the sound we had waited all day to hear: a rattle. Just to our left on the white sandy beach sat, not one, but two, large Eastern diamondbacks. I was in awe. It sent our group into an organized frenzy of snake tongs and buckets, and just a few minutes later, all our efforts had paid off. We had successfully captured island-living C. adamanteus and extracted their venom for research. After twelve hours of hiking across Little St. George’s unforgiving landscape, we found our target species less than 50 meters from our boat dock. I was tired, but elation was the only emotion I felt.

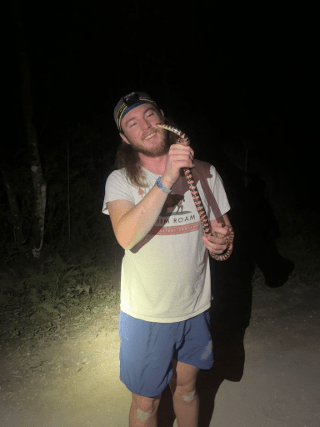

However, this experience had a bigger impact on me than just finding an iconic species. The group of herpetologists I tagged along have since become close collaborators and coauthors. That Florida summer day set me down the path of graduate school where I too, studied snakes and venom evolution that you can read about in an IOB publication. To this day, I remain in awe of serpents.

About me:

I have been completely and totally obsessed with snakes, their conservation, and their ecology and evolution from a very young age. I believe working at the intersection of ecology and evolution plays a crucial role in understanding and protecting the species I cherish so dearly. Currently, I am a Ph.D. student at San Diego State University where I am studying urban ecology and evolution of snakes in Greece’s Cyclades Islands. My M.S. work focused on the evolution of garter snake (Thamnophis) venom, and how dietary ecology shaped its components.

Find out more about my work at https://tuckerheptinstall.weebly.com, follow me on Instragram and BlueSky @hippieherper, or contact me at tuckerheptinstall@gmail.com.

& watch Tucker’s SICB/IOB YouTube talk on his paper and his work in Greece.